9.4 Sweerts’ Use of Underdrawing

In 17th-century Flemish painting, next to an underpainting, an underdrawing was often used to prepare the composition on the canvas. The common practice was that the underdrawing was often applied in white chalk or a suspension of white chalk in water on the double, grey over red ground. According to Wallert and De Ridder, academic tradition also prescribed this method.1 The refractive index of chalk is very close to that of (linseed) oil, which means that once the chalk comes in contact with oil, it can no longer be seen with the naked eye. An underdrawing executed in white chalk thus disappears when the paint layers are applied on top.

In (technical) art historical literature on Sweerts, it is assumed that he prepared his compositions with an underdrawing in white chalk or a white chalk suspension. In the context of the 2002 research project into the working methods of Sweerts, Wallert and De Ridder made a reconstruction of Sweerts’ A Woman Spinning from the collection of Museum Gouda [20].2 This reconstruction is now on view in Museum Gouda, in the so-called ‘Kindermuseum’. In this reconstruction [21], Wallert and De Ridder added an underdrawing stage in white chalk [22]. This assumption that Sweerts applied an underdrawing in white chalk, however, is not based on evidence found from examination of Sweerts’ painting.

In the case of A Woman Spinning, no trace of a white chalk underdrawing can be found in the painting with the naked eye. Neither can a trace of such an underdrawing be found in the results of MA-XRF scanning of A Woman Spinning. Additionally, it remained unknown to what extent Sweerts made use of an underdrawing: did he only apply summary indications, or did Sweerts meticulously drew the contours of all objects and figures that then only needed to be filled in with colours?

20

Michael Sweerts

A woman spinning, c. 1656

Gouda, Museum Gouda, inv./cat.nr. 55250

21

Reconstruction of Sweerts’ A Woman Spinning, on view in the Kindermuseum in Museum Gouda. Photography by Kirsten Derks

22

Detail of fig. 22

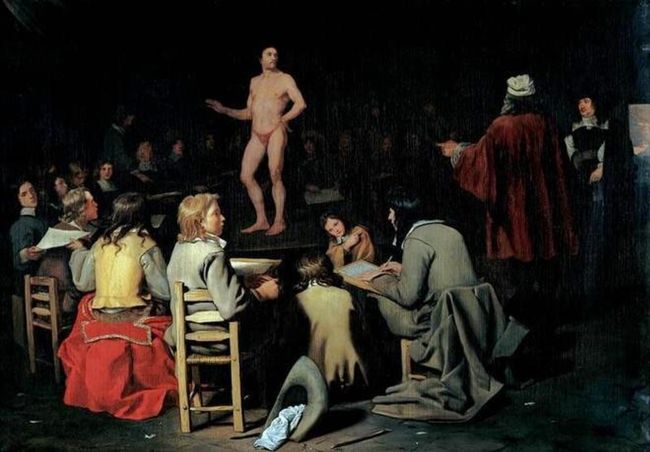

The results of a recent analysis of The Drawing Academy by Sweerts gave more information about the way Sweerts prepared his compositions. The Drawing Academy shows an interior in which young pupils sit in a circle around a table [23]. Upon the table, a nude male model is posing. The pupils are drawing from life. In the right background, the master painter is depicted in conversation with a gentleman dressed in black. The artist is wearing a dark red cloak and a typical painter’s hat. In the foreground, a few drawing tools and a hat are scattered around the floor. The painting presents the last stage of a course in drawing, namely drawing from a nude model. This was considered essential in learning the principles of proportion and anatomy. Before this final stage, the drawing student had to copy the work of other masters and draw from plaster casts and (marble) statues. The boys in the foreground do not seem to be typical pupils found in an artists’ studio. Their fancy clothing reveals that they are young gentlemen. In the mid-17th century, it was common for well-to-do citizens to master the art of drawing as part of their education.3 In this respect, this painting can be seen as a commentary of Sweerts on the formal education in the arts.

In January 2020, MA-XRF scanning of The Drawing Academy was carried out.4 In the lower left corner of The Drawing Academy, an unusual calcium signal was detected. Along the contours of the figures, thin and sketchy lines rich in calcium were revealed with MA-XRF scanning [24]. Visually, these lines are reminiscent of a sketch.

23

Michael Sweerts

Drawing Academy, c. 1655

Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, inv./cat.nr. 270

With a calcium-based material, the artist seemed to have indicated the contours of the boys in the left foreground. He drew their faces – including eyes, nose and mouth – and indicated their hair and clothing. The calcium signal in these overpainted outlines is very clear, which is quite exceptional in MA-XRF images, as the low energy Ca-K signals are readily absorbed by superimposed layers. This is likely due to the thinness of the paint layers, which contain a relatively large amount of radio transparent carbon black pigments, applied by Sweerts. The Drawing Academy is painted with very thin paint layers, and in many areas the ground layer has been left exposed. Microscopic examination of The Drawing Academy has been carried out in order to gain more information about the material used by Sweerts to apply this underdrawing.5 However, nothing corresponding with the Ca-K signal was found [25]: the thin lines in the Ca-K map do not correspond with the paint applied in this area. The calcium signal thus cannot come from a paint layer containing bone black, but rather comes from a material present underneath the paint layers. The thin lines from the Ca-K map were not visible. This indicates that it is very likely that Sweerts used white chalk for his underdrawing, as white chalk becomes invisible to the naked eye when in contact with oil paint.

The Ca-K map shows that this underdrawing was applied in a rapid and sketchy way, while it still remains a rather detailed character. Sweerts indicated the contours of the figures with thin lines. In some areas, Sweerts went over the same line multiple times, suggesting that Sweerts drew this underdrawing freehand. The underdrawing was not transferred from a drawing on a separate support.

Notes

1 Wallert/De Ridder 2002, p. 40.

2 Michael Sweerts, A Woman Spinning, c. 1656. Oil on canvas, 52.5 x 42.5 cm. Museum Gouda (Gouda, Netherlands), inv.no. 55.250.

3 Emmens 1965, p. 1a-b.

4 For scanning, the AXIL scanner was used. The painting has been scanned with the following parameters: step size 650µm and 160 ms dwell time per pixel. A detail of the painting has been scanned with a step size of 300µm and dwell time of 200 ms per pixel.

5 Microscopic examination has been carried out by Kirsten Derks in the conservation studio of the Frans Hals Museum, in February 2020.