8.4 The Key is in the Music Book(s)

As shown above, the illustrations in the Roman music book contain several elements that also appear in the separate drawings by the same artist. Evidently, this collection of cantatas was not the only music book the artist decorated. The series of four drawings with gilt initials auctioned at Swann Galleries in 2021 [39-42] undoubtedly had the same function. They have a similar small size to the decorations of the Roman songbook and also feature the thick framing line. Moreover, the rounded notes of the staves on the verso are visible through the paper, in the area of the sky, where the representation is less filled with detail.1 The same applies to the series of four drawings offered for sale in 1972 by Wiliam H. Shab in New York [31-34].

Unfortunately, the questionable practice of removing illustrations from music manuscripts was not rare. This generally took place at least a century after their creation.2 Far beyond their original context, the volumes have lost their original sentimental value and have become semiophore.3 Removing the illustrations usually happened when the owner saw commercial opportunities and decided to sell the drawings separately.

Cantatas manuscripts and repertoire

Secular cantatas are vocal compositions for one or more voices and instrumental accompaniment.4 Professional scribes copied such cantatas piece by piece in their neatest handwriting. Composed at or for special occasions, such as academic meetings, visits by dignitaries and weddings, a limited number of people enjoyed the performances of cantatas, which were played in a chamber music-like setting.5

The subject of secular cantatas is usually love in all its aspects and consequences. Contemporary or classical literature serve as thematic inspiration, but so do pivotal moments in the lives of the person involved or of the commissioner of the compositions, such as a marriage, the birth of a child, a newly acquired job, retirement from a monastery, to name a few.6 Many music books are eye-catching and feature exquisite bindings to match the exclusive compositions and other embellishments specially crafted for each manuscript. Although the preciousness on the outside does not necessarily match the wealth of ornamentation on the inside and vice versa, many bindings feature ornamentation to accompany the cantatas: calligraphic initials, decorative initials with zoomorphic, vegetal or anthropomorphic motifs, vignettes, or all these in various combinations.

Such an excess of elegance and preciousness indicates that these volumes were intended for collectors. They ordered copies of these music books and their decorations for personal use.7 Such manuscripts were also donated as valuable objects to like-minded collectors. The style of decorations inevitably reflected the interests and mindset of the patron and the cultural context in which they were created.8

39

Master of the Roman Songbook

Carnival in the streets of Rome, c. 1655

London (England), private collection Henry Scipio Reitlinger

40

Master of the Roman Songbook

Two soldiers shaking hands or Castor and Pollux, c. 1655

London (England), private collection Henry Scipio Reitlinger

41

Master of the Roman Songbook

Vrolijk gezelschap in een tuin, c. 1655

London (England), private collection Henry Scipio Reitlinger

42

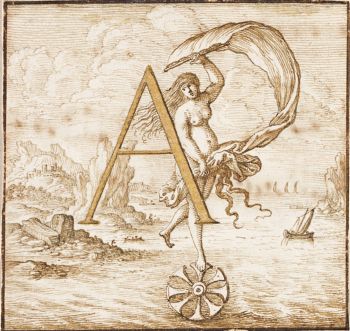

Master of the Roman Songbook

Fortuna, c. 1655

London (England), private collection Henry Scipio Reitlinger

31

Master of the Roman Songbook

Landscape with resting shepherd shepherd and buildings, c. 1650

New York City, art dealer William H. Shab Gallery Inc.

32

Master of the Roman Songbook

River landscape with a couple conversing, c. 1650

New York City, art dealer William H. Shab Gallery Inc.

33

Master of the Roman Songbook

Landscape with Orpheus and the animals, c. 1650

New York City, art dealer William H. Shab Gallery Inc.

34

Master of the Roman Songbook

River landscape with hunter, c. 1650

New York City, art dealer William H. Shab Gallery Inc.

The Casanatense volume

The fascinating manuscript MS2478 entered the collection of the Casanatense Library in 1844, when it was bequeathed by musicologist Giuseppe Baini (1775–1844), alongside some 20 other similar objects.9 A crimson chenille pouch protects the book, which is bound in Moroccan brownish leather with gold decorations [56]. The pages measure 10 x 27 cm, identifying the format as Carta da ariette. The design on the cover is in Rospigliosi style and is attributed to the workshop of Andreoli.10 The scribe's handwriting is plain and neat. In the specific literature, he appears as Scribe B.11

Almost nothing is known about the context of the manuscript's production. All the composers and poets represented, including Luigi Rossi (1597–1653), Giacomo Carissimi (1605–1674), Marc'Antonio Pasqualini (1614–1691), Mario Savioni (1606/8–1685), Giovanni Marciani (c. 1605–1663), were active in Rome in the first half of the 17th century. During the same period, writer B also wrote other compositions, some by these same composers.12

The function of the vignettes in the Casanatense manuscript is mainly decorative. The drawings, measuring about 6 x 8 cm, have a thick line frame and appear on the first page of each cantata, on the left side of the page. For many cantata books, it is impossible to determine whether the decorations came before the music or vice versa, since the craftsmen involved in their execution – scribes and decorators – did not work on the same pages at the same time.13 Consequently, the texts of the Casanatense cantatas do not refer to the subjects of the respective drawings. Seven vignettes depict scenes from Ovid's Metamorphoses;14 four contain episodes from other literature;15 ten others show landscapes with prominent genre scenes in the foreground;16 the remaining seven show views of Rome during Carnival.17 Several of these give reason to situate the artist in Rome around the mid-17th century.

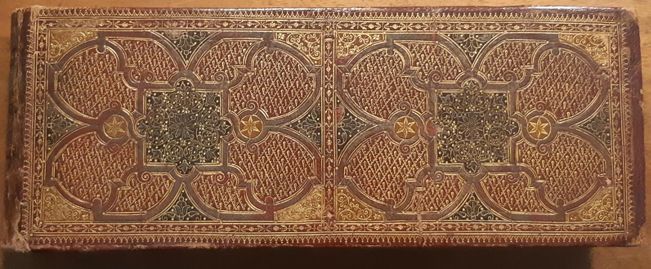

56

Master of the Roman Songbook

Manuscript with secular cantatas by Italian composers, 1652 or 1653

Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, inv./cat.nr. Ms2478

The Roman Carnival

The scene with the horse race seen from Piazza Colonna [5] represents the palio of the Berbers, a horse race that started in Piazza del Popolo and ended in Piazza Venezia, passing through via del Corso, then called via Lata.18 This palio was one of the most attended events of the carnival, and was sometimes depicted by artists, for instance by Paul Bril in the Allegory of the months January and February [57] engraved by Aegidius Sadeler II (1568–1629) in 1615. An illustration of the event is also included in Pompilio Totti's (c. 1590-ca. 1644) city guide Ritratto di Roma Moderna from 1638 and in later editions.19

5

Master of the Roman Songbook

View on piazza Colonna and via Lata in Rome, 1652 or 1653

Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, inv./cat.nr. MS2478

57

Aegidius Sadeler (II) after Paul Bril

January and February, 1615

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-7031

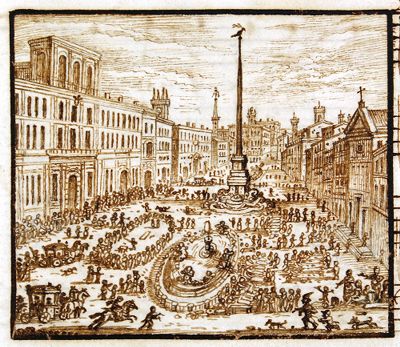

Vignette number 12 [12], showing the Piazza Navona seen from the south side, contains details that are particularly relevant for the dating of the series. On the left, the Pamphilj residence is clearly visible, and in the middle of the square the family's obelisk adorns the already completed Bernini fountain. A swarm of people fills the square.20 The absence of the façade of S. Agnese in Agone suggests that the manuscript must date somewhere between 1651 and 1655.21 While the inauguration of the Four Rivers fountain took place on 12 June 1651, Palazzo Ornano, the characteristic tower-palace on the left at the corner of via dell'Anima, was bought by the Pamphilij family and demolished in October 1653 to make way for the church of Sant'Agnese.22 Therefore, the carnival depicted must have taken place in 1652 or 1653.

12

Master of the Roman Songbook

View of Piazza Navona in Rome, 1652 or 1653

Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, inv./cat.nr. MS2478

Sacred Procession

Some other vignettes in the songbook also contain clues concerning the date of execution. These are the drawings showing episodes of the procession called Visita alle Sette Chiese, a traditional pilgrimage established in the Middle Ages and revived in 1553 by St Philip Neri (1515-1595) in order to counterbalance the profane revelry of the Carnival in the city centre [27-28].23 Pilgrims visited the seven churches of the Holy Year following a prescribed itinerary on Wednesday and Fat Thursday.24 On the second day of the walk, the pilgrims rested in the vineyards of the Villa Mattei, or Celimontana. The Oratorian friars then organised a frugal meal with food and drinks for all participants.25 Sacred music pieces and laudi were performed during the walk from church to church and inside the buildings during the usual rituals.26

There is also evidence that vocal and instrumental music performances took place in the Celimontana gardens.27 They included trumpets, zinks (cornettos), lutes, a choir and an organ that was on loan from the nearby church of St Nereo, as can also be seen in an anonymous painting from the late 17th century in the sacristy of the church of the Navicella, adjacent to the premises of Villa Mattei.28

Vignettes 25 and 26 show two moments of the rest in the garden of the Celimontana [25-26]. In the first, the pilgrims dance to the tune of violins, tambourine and guitar, while the villa is recognisable in the background. Although there is no specific mention of dancing in contemporaneous accounts of the visit, it is conceivable that the pilgrims also enjoyed such relaxation in addition to spiritual meditations.29 In the second drawing, a servant provides a couple of pilgrims with lunch, while another couple relaxes, sitting on the ground.30 In the far right background, just beyond the hill, is the pyramid of Cestius, and the church of S. Paolo fuori le mura, one of the stages of Thursday's pilgrimage.

According to the literature, the pilgrimage to the seven churches could not take place every year because of plague epidemics, holy years, sede vacante, or bad weather conditions. For unknown reasons, the 1653 pilgrimage did not take place, at least there are no records of the number of participants. 31 Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the drawings refer to the year 1652.

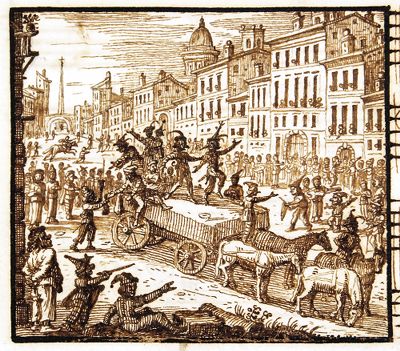

27

Master of the Roman Songbook

Carnival in the streets of Rome, 1652 or 1653

Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, inv./cat.nr. MS2478

28

Master of the Roman Songbook

Carnival in the streets of Rome, 1652 or 1653

Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, inv./cat.nr. MS2478

25

Master of the Roman Songbook

Rest in the gardens of the Villa Celimontana, 1652 or 1653

Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, inv./cat.nr. MS2478

26

Master of the Roman Songbook

Rest in the gardens of the Villa Celimontana, 1652 or 1653

Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, inv./cat.nr. MS2478

Notes

1 I am grateful to Swann Galleries for providing photos of the verso of the vignette, confirming their provenance from an Italian vocal music manuscript.

2 I have recently discussed an album containing decorations stripped from four different volumes of cantatas at the 28th yearly symposium of the Societá Italiana di Musicologia (Rome, 2021). The drawings were disassembled between the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century.

3 Ago 2006, XVI.

4 Timms 2001; Sciommeri 2021, p. 2–12.

5 Goudriaan 2013; Jeanneret 2009; Rostirolla 2001; Ruffatti 2007 and Ruffatti 2015, p. 67. Cantatas were also published though only around 140 editions are documented. Giovani 2017, p. 37.

6 Brumana 2005; Murata 2003.

7 Traces of payments for manuscript decorations are scarce. Lionnet 1980, p. 302.

8 Morelli 2015, p. 195–196; Murata 2015, p. 203.

9 Paton 1978.

10 Hobson 1991; Ruffatti 2007.

11 Ruffatti 2007.

12 Murata 2003; Ruffatti 2007.

13 Jeanneret 2009.

14 RKDimages 301888, 301895, 301897, 301898, 301900, 301905, 301910.

15 RKDimages 301885, 301896, 301901, 301907.

16 RKDimages 301885, 301886, 301887, 301893, 301902, 301903, 301904, 301906, 301908, 301909, 301911.

17 RKDimages 301892, 301894, 301899, 301912, 301913, 301914, 301916.

18 Ademollo 1883, p. 59–63; Clementi 1899, p. 370 ff.

19 Totti 1638, view of Palazzo Caetani, p. 334.

20 D´Amelio/Marder 2014.

21 Murata 2003.

22 Lenzo 2012, p. 118–119.

23 Lazzarini 1947.

24 The churches are: S. Giovanni in Laterano, S. Pietro in Vaticano, S. Paolo fuori le Mura, S. Maria Maggiore, S. Lorenzo fuori le Mura, S. Croce in Gerusalemme, S. Sebastiano fuori le Mura.

25 Lazzarini 1947; Mancini/Montanari 2000; Zimei 2006.

26 Zimei 2006, p. 285–286; 295.

27 Zimei 2006, p. 298.

28 Lazzarini 1947, p. 59–60.

29 Zimei 2006, p. 288–289.

30 The lunch consisted of bread, salami, egg, cheese, an apple, and watered wine. Lazzarini 1947, p. 45–62.

31 Lazzarini 1947, p. 65–66.