5.1 Brussels Artists among the Fiamminghi

Passeri’s biography of Cousin remains frustratingly silent about the nature of the opportunities provided by Duquesnoy, but he did mention another individual who assisted the twenty-year old artist: Flemish banker and merchant Pieter Visscher, known in Italy as Pietro Pescatore.1 Visscher held a prominent role in Rome’s Flemish community and had given Duquesnoy his first significant commission when he arrived in the city.2 The friendship and support of both Duquesnoy and Visscher would have been instrumental for easing Cousin’s entry into Rome, laying the foundation for his future successes by providing introductions to potential patrons and artists. By the mid-1620s, Duquesnoy was well established in the city and belonged to a circle of artists and patrons who embraced his passion for antiquity and Greek classicist style. He would soon receive prominent sculptural commissions for the churches of Santa Maria dell’Anima and Santa Maria di Loreto — the former likely aided again by Visscher — but in 1626 Duquesnoy was busy elsewhere: he was part of the team of sculptors assisting Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) in the construction of the Baldacchino in St. Peter’s, placing him, quite literally, in the religious and artistic heart of papal Rome.3

Cousin, though an unfamiliar name to many today, also became a prominent and respected figure in the city.4 By the early 1630s, he began receiving commissions for both large and small-scale works from princely and papal patrons, including the Cesi, Pamphilj, and the Chigi, practicing a refined, subtle style that reflected his close study of nature as well as his knowledge of Duquesnoy’s artistic approach. Like the sculptor, Cousin was a member of the Accademia di San Luca, Rome’s official academy of art, and eventually rose to the rank of principe, or director, in 1651. He was only the second Netherlander to hold the position in the Accademia’s history, an honor Duquesnoy was nominated for, but never elected.5

The helping hand that Duquesnoy had offered Cousin was not an isolated incident. Similar patterns of friendship characterized the experience of two other Brussels artists: Karel Philips Spierincks, who arrived in Rome in 1624 and formed a long and multifaceted friendship with Duquesnoy, and Michael Sweerts, who traveled south two decades later and found an ally in Cousin.6 Unlike the majority of Dutch and Flemish artists who came to Rome for short periods of time to study the art of antiquity and the Italian masters before returning to the north, these artists either settled permanently in the city or chose to stay for a significant part of their careers.7 They integrated themselves into the city’s patronage and institutional networks, demonstrated a strong commitment to the Accademia di San Luca, and achieved success among their peers. Their classicizing and academic interests, as well as their shared cultural and religious background in Catholic Brussels, created a common ground that united them in ways that were distinct among their fellow Fiamminghi.

Netherlandish artists had long relied on expatriate communities and personal connections to help ease their transitions into foreign cities, Rome above all.8 ‘Home’ churches or national confraternities, such as San Giuliano dei Fiamminghi (serving the Flemish community), Santa Maria dell’Anima (serving the Netherlandish and German communities), and Santa Maria della Pietà in Campo Santo dei Teutonico (serving the German and Flemish communities), had traditionally served as places of refuge for pilgrims entering the city. They developed into centers of community for the Fiamminghi, offering camaraderie alongside practical and spiritual support.9 By the second quarter of the 17th century, the Bentvueghels, or Schildersbent, fulfilled a similar, albeit more secular role. This informal confraternity of Netherlandish artists, which formed around 1620, was a social and cultural group that provided support, friendship, and solidarity for Northerners in the city [2].10 While much attention has been given to the boisterous rituals and satirical nature of the Bent’s activities, including the mock baptismal ceremonies upon the entrance of new members, more recent scholarship has shown how the group was an effective professional network that benefitted its artists in important social and economic ways.11

With the exception of Cousin, who became a member of the Bentvueghels in 1626 (with the bentnaam Gentile), Duquesnoy, Spierincks, and Sweerts never joined the organization.12 Their absence from the group has been viewed as an indication of their divergent artistic interests and ambitions, but as the case of Cousin and others suggest, such divisions were hardly maintained in reality.13 Artists from within and outside of the Bent socialized and aided one another at various points in their careers, and a lack of involvement does not appear to have been a disadvantage to their success — often quite the opposite.14 On the other hand, participation in the Bentvueghels did not exclude artists from membership in other organizations such the Accademia di San Luca or the national churches of San Giuliano dei Fiamminghi, Santa Maria dell’Anima, or Campo Santo, of which Cousin, Duquesnoy, and Spierincks served on their respective administrations at various points in the 1630s and 1640s.15

Despite the prominence these artists enjoyed in the 17th century, they have remained on the margins of our understanding of the Netherlandish experience in Rome. Part of this lacuna derives from a neglect to address Brussels as an artistic center,16 but it also results from the challenges inherent in situating Cousin, Duquesnoy, Spierincks, and Sweerts—Flemish artists who spent the majority of their careers in Italy— within a single geographical or art historical context.17 Their long stays in Rome have fallen outside of the traditional framework of the Fiamminghi: they resist categorization within the Bentvueghels and the Bamboccianti, and they sit uneasily within the ‘conflict’ that arose between Netherlandish artists and the Accademia di San Luca in the 1630s.18 Since G.J. Hoogewerff’s seminal studies on the Bentvueghels and the Accademia in the early 20th century, the relationship between these two groups has been seen as highly contentious.19 The Bent, according to Hoogwerff’s view, formed in reaction to the Academy, providing solidarity for Netherlanders in the face of the Roman establishment.20 This long-standing characterization, however, calls for a fresh examination. Through the example of these Brussels artists, this contribution seeks to show how the dynamics between the two groups were more nuanced and fluid.

Examining the careers of Brussels artists in Rome thus offers an alternative perspective on the predominant narratives around the Fiamminghi. The ties among these artists were not only informed by their ‘Netherlandishness’, a collective cultural distinctiveness that emerged from being foreigners in a host city, but more immediately by their Brussels origins, which gave them a distinct sense of patria.21 Brussels impacted their artistic and cultural identities in significant ways, and contributed to how they navigated, integrated, and ultimately succeeded abroad. At the same time, this article demonstrates how this group also formed important bonds and friendships with Italian and French artists, moving easily among these different communities in the Eternal city.

Brussels origins

Duquesnoy, Cousin, Spierincks, and Sweerts would have experienced a certain ease in settling into Rome. Having come from a Catholic-Habsburg stronghold in the North, they were predisposed towards Rome’s artistic culture and patronage networks. In the early decades of the 17th century, Brussels experienced an explosion of artistic creativity in the wake of the iconoclastic riots that took place across the region at the end of the 16th century. The Habsburg Archdukes Albert (1559-1621) and Isabella (1566-1633), who had been installed as rulers in 1599, ushered in a period of rebuilding and revitalization that made Brussels an important center of the Counter-Reformation.22 Like their Habsburg predecessors, the Archdukes embraced the visual language of antiquity as an expression of the authority of court and church, and largely employed artists who had worked in Italy or who were knowledgeable in the antique tradition. The appointment of the architect, painter, and antiquarian Wenzel Coebergher (ca. 1560-1634) [3] as their first court artist in 1605 — four years before Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) — was a testament to their ambitions.23 Coebergher, who had spent twenty years in Naples and Rome, became critical in shaping the city’s artistic landscape with a renewed visual language, evident in his most important project for the Archdukes, the pilgrimage church of Scherpenheuvel, which encompassed painting, sculpture, and architecture.

This artistic and cultural environment would have significantly impacted the young Duquesnoy, who began his career by training with his father, the sculptor Jérôme Duquesnoy I (ca. 1570-1650), around 1611-1612.24 Jérôme the Elder worked regularly for the archducal court under the auspices of Coebergher on major sculptural commissions both within and outside of the city. Although few of these sculptures survive, the monumental tabernacle in the Church of St. Martin in Aalst [4], just outside of Brussels, for example, demonstrates the scope and character of Jérôme the Elder’s work, as well as his reception of a classicizing idiom.25 By 1618, Duquesnoy had decided to undertake the journey south. He sought the support of the Archdukes, and submitted a petition requesting a financial stipend for two to three years of study in Rome. According to the document, this period would enable him to the study the antique and improve his art (‘pour s’esvertuer davantaige au faict de son art’).26 The sculptor’s devotion to antique sculpture once he settled in the city was indicative of his Brussels training, then stimulated by a direct and ongoing encounter with Rome’s monuments and the dialogues that ensued with like-minded artists.

In comparison to Duquesnoy, little is known about Cousin, Spierincks, and Sweerts’ education and training in Brussels. Spierincks registered as a pupil of the painter Michel de Bordeaux (1579-1627) in 1612, and Cousin is documented as an apprentice of Gilles Claessens in 1618.27 No records document Sweerts’ registration in the guild or his artistic training, but the painter Theodoor van Loon (1581/2-1649) [5], who spent his career between Brussels and Rome, was likely a pivotal artistic model for the young painter’s development of a classicizing style and poignant naturalism.28 Despite the lack of documentation on these artists’ early careers, they each would have encountered the distinctive blend of Flemish and Italian traditions that took shape across Brussels’ landscape, and witnessed the ways in which a classicizing visual language served the needs of the Counter-Reformation. Their motivations for traveling south would have been similar to Duquesnoy’s, and they probably realized that Rome held rich potential in the short and long-term.29 These circumstances must have impacted their decision not to return north immediately — or at all. Although Duquesnoy, for instance, was presumably expected to return to the Netherlands in the service of the court, he never did. Whether this decision reflected the changing political circumstances after Albert’s death in 1621, which reverted rule of the Southern Netherlands back to Spain, or resulted from abundant opportunity (or more likely a combination thereof), it gave rise to Duquesnoy’s prominent and respected place within the Roman art world.

2

Anonymous North-Netherlandish, c.1623-1624

Portraits of Giovanni di Filippo del Campo (c. 1600-after 1638), Pieter Anthonisz. van Groenewegen (c. 1600-1658), Joost Campen (1595-after 1640) and Simon Ardé (c. 1595-1638), members of the Schildersbent in Rome

paper, black and red chalk, grey wash 280 x 423 mm

incribed below : Aliaes Braeff / Peter Groenewegen / Aliaas Leeuw / Joost Kampen van Amsterdam / Alias Stoffade / Symon van Antwerpen / Alias den Toovenaar

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv.no. 8C

3

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Wenzel Coebergher (1560-1634), c. 1630

Amsterdam, Amsterdam Museum, inv./cat.nr. A 10151

4

attributed to Jerôme Du Quesnoy (I)

Sacrament Tower, dated 1604

Aalst (Oost-Vlaanderen), Sint-Martinuskerk (Aalst)

5

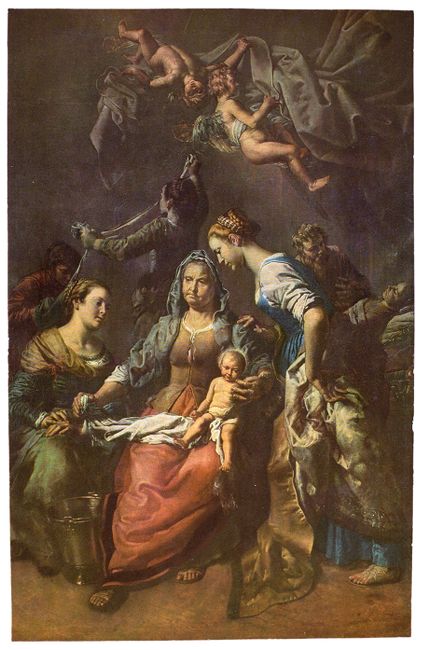

Theodoor van Loon

The birth of Mary (8 September), c. 1622

Scherpenheuvel (Scherpenheuvel-Zichem), Basiliek van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van Scherpenheuvel

Notes

1 ‘Quel Maestro Fiammingo chiamato Pietro procuro sempre di sollevare quelli della sua nazione’. Passeri 1995, p. 242.

2 Visscher commissioned a marble sculpture of a nude seated Venus nursing Cupid (now lost). Bellori 2005, p. 228; Passeri 1995, p. 103-104. On Pescatore: Blanchardière and Bodart 1974; Boudon-Machuel 2005, p. 26-27; Borsoi 2009. Visscher’s involvement with the Flemish artistic community deserves a fuller study; in this article, he plays a supporting role.

3 In 1628 Duquesnoy received the commission for the tomb of Adriaan Vrijburgh in Santa Maria dell’Anima, followed by the tomb for Ferdinand van den Eynden in the mid-1630s. Visscher was part of the administration of the church. By late 1629, Duquesnoy had also received the commission for the St. Andrew, one of the four colossal sculptures for the crossing of St. Peter’s. The commission for the Saint Susanna for Santa Maria di Loreto followed shortly thereafter. Boudon-Machuel 2005.

4 Van Puyvelde 1950, p. 188-193; Van Puyvelde 1958; Bodart 1970, p. 154-167.

5 Cousin was preceded in this position by the Antwerp painter Paul Bril (1553/4-1626), who served as principe in 1621. Hoogewerff 1913, p. 58, 61. Duquesnoy was nominated for the role of principe in 1633, 1640, and 1641. Hoogewerff 1913, p. 54; Boudon-Machuel 2005, p. 99.

6 On Spierincks: Blunt 1960; Bodart 1970, p. 137-140; Squarzina Danesi 1999; on Sweerts in Rome: Yeager-Crasselt 2015.

7 Duquesnoy died in 1643 in the port of Livorno on his way back the Netherlands. He had recently accepted an offer from the King of France to establish an academy of sculpture in Paris, but illness prevented him from making it there. Spierincks died in Rome in 1639. Both Cousin and Sweerts eventually made their way back to Brussels in the 1650s.

8 Scholten/Woodall 2014. Comparable communities of foreign artists existed in Venice, Florence, Naples, London, and Madrid. On Netherlandish artists in Naples, which raise a number of similar issues, Osnabrugge 2019.

9 This included lodging, hospital care, and ultimately burial. Vaes 1919; Bodart 1981; De Groof 1988; Schulte Van Kessel 1995.

10 Hoogewerff 1952; Verbene 2001; Janssens 2001; Cappelletti/Lemoine 2014; Downey 2015; Baverez 2017.

11 Verbene 2001; Downey 2015; Baverez 2017.

12 Sandrart 2008-2012: TA 1675, II, Buch 3 (niederl. u. dt. Künstler), S. 320; Passeri 1995, p. 244. Boudon-Machuel 2005, p. 26, raises Judith Verbene’s (unpublished) hypothesis that Duquesnoy may have been a Bent member because of his frequent contact with the group.

13 The little-known Brussels painter Simon Ardé (ca. 1596-1638) was also a Bent member.

14 Discussion follows below.

15 Their involvement in these confraternities expands beyond the scope of this paper, but demonstrates an important aspect of their integration into Rome’s institutions. Cousin, for example, was active in San Giluiano dei Fiamminghi and served on its administration, while Duquesnoy and Spierincks were part of the administration of Campo Santo. In the 1630s, all three Brussels artists then in Rome — Duquesnoy, Spierincks and Cousin — received commissions for Santa Maria dell’Anima, a church in which Pieter Visscher played a reoccurring role. Spierincks had received a commission to complete four paintings for the church’s sacristy in 1637, but the works were not completed before his death. Afterwards, Louis Cousin, Justus de Pape, Gills Backarel, and Johannes Hoeck were brought in to complete one painting each for the commission. None of these works survive. Hoogewerff 1913, p. 522, 707, 708, 711, 715.

16 Brussels has long been overlooked as an artistic center in favor of Antwerp, though this is slowly changing. For a summary of recent scholarship: Van der Stighelen/Kelchtermans/Brosens 2013; Yeager-Crasselt 2015; Brosens/Beerens/Cardoso/Truyen 2019.

17 Boudon-Machuel 2012 addresses these challenges in the context Duquesnoy’s career. An important contribution to this broader subject, in regard to addressing the relationship between Flemish and Italian artistic communities in Rome and some of these related issues, is Thompson 1997.

18 Much confusion has arisen in the literature between the Bentvueghels and the Bamboccianti. The latter refers to a group of artists who painted low-life genre scenes of Roman street life following the manner of Haarlem artist Pieter van Laer. Although they found success among Italian patrons, artists associated with the Accademia disparaged the Bamboccianti’s choice of subject matter, provoking artistic debates that came to a head around mid-century. Many Bamboccianti were members of the Bentvueghels, but one did equate to the other. These nuances are discussed in Yeager-Crasselt 2015; Downey 2015.

19 Hoogwerff 1926; Janssens 2001. Hoogewerff primarily attributed the conflict between the two groups to stylistic differences and the Netherlanders’ reluctance to pay annual taxes to the Academy, discussed further below.

20 Hoogwerff 1926; Hoogewerff 1952.

21 De Groof 1988, p. 93 discusses the distinction between patria and natione; the former (vaderstad) signifying the place where one was born, and the latter a national community (vaderland). In a number of instances, such as the stati d’anime, they are specifically referred to as coming from Brussels, i.e. Luigi Primo da Bruxelles fiammingo pittore.

22 De Maeyer 1955; Thomas/Duerloo 1998.

23 Meganck 2014.

24 Patigny 2015, p. 171n23.

25 Patigny 2015. Other large-scale projects included sculptures for the Churches of St. Michael and St. Gudula and the archducal hunting lodge in Tervuren, as well as the restoration of antique sculpture.

26 Boudon-Machuel 2005, p. 19n60.

27 Both artists registered as master painters in the Brussels guild in 1622 and 1624, respectively, before leaving for Rome.

28 Yeager-Crasselt 2015, p. 37-41; Vlieghe 2018, p. 102.

29 These artists continued a long tradition of Flemish artists making the journey south, from the sixteenth-century sculptors Jean Mone, Jacques Dubroeuq, and Cornelis Floris – to name but a few – to contemporaries in Brussels such as Wenzel Coebergher and Jacques Francquart, whose appointments at the Brussels court had demonstrated the valuable impact of a Roman journey. On the Netherlandish artists traveling south in the 16th century: Allart et al. 1995; De Jonge 2010.