4.4 The Spanish Faction, Giovanni Vasanzio and Van Honthorst

So far, three altarpieces by Van Honthorst for churches of the Discalced Carmelites have been examined and the connection between the order and the Dutch painter has been recognized, but the question remains as to how the order, or Father Domenico, first became acquainted with the young foreign painter, who had no experience of public work. In considering the issue, it is first worth examining the relationship between the newly established order and Pope Paul V.

As we have seen, the Discalced Carmelites grew rapidly in power after the foundation of the order. Under the papacy of Clement VIII (papacy: 1592-1605), however, that growth was slowed when the Pope deemed the order to be a mere Congregation and deprived it of its superior-general.1 That situation was reversed by Paul V during the first two decades in the seventeenth century. The new Borghese Pope restored the rights of the Discalced Carmelites, supported the order in many ways, and beatified its founder Teresa of Avila in 1614.2 The construction of their church, San Paolo a Termini, was also made possible under his protection. For example, the Novitiate that had been planned for the site was eventually transferred to Monte Compatri, the territory of the Borghese family.

Meanwhile, Domenico di Gesù Maria was playing a leading part for the Discalced Carmelites.3 Born in Aragon in 1559, he participated in the reform of St Teresa in 1589. Summoned to Italy in 1604, he then occupied several important offices in Santa Maria della Scala, and in 1612, founded the convent of conversion of St Paul, whose headquarters were located in San Paolo a Termini. From 1617 to 1620, he was general of the order. As if showing their gratitude for the Borghese’s protection, the clergy of San Paolo a Termini offered the family the famous Hermaphrodite sculpture found in the church’s garden in 1619. And again, in return, the Borghese paid for the completion of the façade of San Paolo a Termini, and Paul V appointed Domenico a superior general in the imperial army when they fought the Protestants near Prague in 1620. In sum, Paul V and the Discalced Carmelites seem to have entered into an alliance that was political as well as religious.

The alliance was not only between the two parties. Paul V was elected at a conclave of 1605 with strong support from the Spanish. In return, he rewarded his supporters in many ways, such as beatification or canonisation of those who were popular among Spaniards and awarding benefits to the related parties. The protection of the Discalced Carmelites was included in this agenda.

It should be noted as well that the activities of the newly established order involved many architectural projects. For example, in November 1613, Santa Maria della Scala wanted to extend its monastery and tried to obtain a house owned by the brotherhood of Campo Santo. A papal order of expropriation was issued, and it was the Borghese’s architect, Joannes van Santen (Giovanni Vasanzio, c. 1550-1621), who was appointed to make a valuation.4 The agreement was completed successfully, so Vasanzio was in a position to do the Carmelites a favour.

22

studio of Peter Paul Rubens

Portrait of Domingo Ruzzola, called Domenico di Gesù Maria (1559-1630), c. 1621

Geneva, Musée d'Art et d'Histoire de Genève, inv./cat.nr. 1911-64

Although he is better known by his Italianized name, Giovanni Vasanzio, he was born Jan van Santen in Utrecht. Nothing is known about his activity in his native city, but in Italy he became an assistant to Flaminio Ponzio (c. 1560-1613), the Borghese family architect, and worked as a carpenter (falegname),5 or cabinetmaker.6 After Ponzio’s death in 1613, he took on the latter’s unfinished works and his position as architect. He also collaborated with Carlo Maderno on some projects such as Palazzo Borghese. Unfortunately, little is known about his personal life, but it is interesting that an architect from Utrecht who had only recently risen to power was associated so closely with the Discalced Carmelites. As mentioned above, in late 1613 the order had an interest in real estate, and the pope and Vasanzio ensured that they had a favourable contract. Just after that, the young painter from Utrecht obtained the commission for the altarpiece for this order in Genoa, the first in a series.

What, though, could have been the possible connection between the architect and the young painter? Unfortunately, their direct contact doesn’t seem to be documented, so we have to rely on the indirect and circumstantial evidence. First, it is easy to imagine that when a compatriot had become the Pope’s architect, an ambitious painter would have tried to gain entry to his circle.7 In addition, Giovanni Vasanzio maintained relationships with his fellow countrymen. For example, in 1616 he was reported to have witnessed a fight in Piazza Navona, when he accompanied his fellow countrymen. He also had a tombstone made for a painter called Willem van Weede (1593-1614) from Utrecht, who died in 1614 at the age of 21.8 Next to nothing is known about Van Weede, other than the fact that he was born in 1593 and left Utrecht for Rome in September 1612. And this deceased painter was a cousin of the Pope’s architect; their mothers were sisters.9

In addition, it seems that the Vasanzio’s family later had a very close connection with Abraham Bloemaert. The architect’s sister, Alidt van Santen, borrowed money from him, and apprenticed her son Johan Michielsz van den Sande to the painter.10 In other words, Bloemaert supported Vasanzio’s sister financially and took his nephew into his workshop. Although the events postdate our cases in Rome, her dependence on the painter by way of borrowing money seems to be evidence of an established family connection between them. It is worth noting that Alidt’s husband, Michiel van den Sande (1583/4-1629/35), was a travel companion of Hendrick ter Brugghen from Milan to Switzerland in 1614.11 So, it is suspected that Willem van Weede might well have been a pupil of Bloemaert and would have known Van Honthorst as well. So it can be hypothesized that the pope’s architect knew Van Honthorst, either through his deceased nephew or some other connections involving Bloemaert, and introduced him to the powerful circle of the Spanish faction around the Borghese. The churches of the newly established order growing in power under the protection of the Borghese were the stage that was offered to the young painter, who was a compatriot of the Borghese’s architect. This may have been how the young Gerard was presented with his first open door to important public commissions.

Of course, there are yet more circumstances to be considered. First, among the many offices that Scipione Borghese held was ‘protector of Germany and the Habsburg Netherlands’ (‘protettore di Germania e il Asburgo Paesi Bassi’), and it should be remembered that the independence of the Dutch Republic was not yet officially recognized in the 1610s. So, broadly speaking, it was appropriate for Borghese to offer a chance to the painter from the Netherlands.12 In addition, it is noteworthy that the Archdukes Albert and Isabella, the governors of the (Habsburg) Netherlands, assiduously supported the Discalced Carmelites. They established a church and a monastery of the order in Brussels and donated to the project of San Paolo a Termini as well.13 To cap it all, Isabella might have met Teresa of Avila in person (though when she was only two years old) and ordered an altarpiece of the saint from Rubens.14 It seems that the latter also made a portrait of Domenico di Gesù Maria.15 The original is now lost but there are works deemed to be workshop copies [22]. Although the apparent connection with the Discalced Carmelites (and Father Domenico) and Rubens occurred only after the painter returned home and began to serve the archdukes, it is possible that he and Domenico met in Rome. As is well known, when Caravaggio’s altarpiece, the Death of the Virgin [23], caused a stir, Rubens mediated with the clergy of Santa Maria della Scala, where Domenico served as master of the novices, and Vincenzo Gonzaga, the Duke of Mantua, who eventually bought the work.

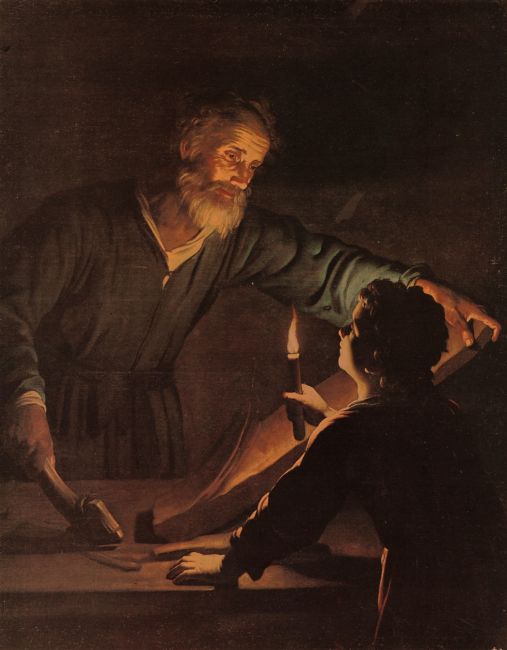

There is another painting that may have some relevance in this context: Christ and St Joseph in his Workshop [24], formerly in the monastery of San Silvestro in Monte Compatri near Rome.16 As Monte Compatri belonged to the territory of the Borghese family, it had been suggested that the painting would have been made for Scipione Borghese. However, Lorizzo proposes that the key person behind the commission must have been Domenico di Gesù Maria, who repeatedly visited the Carmelite monastery and stayed there.17 In any event, it is also a work that was produced in the orbit of the Borghese and the Discalced Carmelites. In the painting, St Joseph holds a hatchet in his right hand and a wooden panel in his left as he gazes with fatherly gentleness at the young Christ, who holds a candle for him. It is certainly far-fetched, but it is tempting to think that the subject matter refers to Giovanni Vasanzio’s career as a carpenter/ cabinetmaker, one of whose patron saints is St Joseph.18 From the stylistic point of view, such as the simple spatial construction and rather abrupt transition from light to dark especially around the nose of Christ and the top extremity of the candle, the work could predate the St Teresa altarpiece in Genoa (or was made at around the same time, and definitely not much later), and it could have been a kind of test piece before he was officially assigned the altarpiece. The subject featuring the patron saint of Giovanni Vasanzio’s profession, the important mediator, and the austere but benign atmosphere of the work would have demonstrated the artist’s gratitude as well as his skill, which made him more than up to the task.

Let us return briefly to Dirck van Baburen. The possible connection between Vasanzio and Van Honthorst has been examined, but is there one in Van Baburen’s case? It is known that he too worked for the Spanish faction around the Borghese, as his patron Cusside was the representative of Spanish king and the Borghese supported San Pietro in Montorio with a donation as well.19 So far, it is only circumstantial, but the possibilities of Vasanzio’s intervention should be further investigated. For example, the design of Pietà chapel was designed either by Carlo Maderno or by Giovanni Vasanzio, with whom Maderno often collaborated. In any event, the timing coincides; the painter obtained the first commission from the Spaniards around 1614, just after Vasanzio attained the post as the Borghese’s architect.20

23

Caravaggio

The death of Mary, 1601-1605

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. 54

24

Gerard van Honthorst

Christ in the carpenter's shop of Joseph, c. 1617

Monte Compatri, Convento San Silvestro (Monte Compatri)

This might explain why Van Honthorst and Van Baburen were much more successful than Hendrick ter Brugghen. The difference in the degree of their success has sometimes been explained on the basis of religious denomination, as the former two were thought to be Catholics whereas Ter Brugghen was not.21 It might well have played a role, but it is also possible that Ter Brugghen returned to the Netherlands just before the heyday of the pope’s architect. Recently, though, the research of Gregor Weber made it clear that Ter Brugghen studied not only Ribera, but also works of Alonzo Rodriguez (1578-1648), which can be interpreted as an interest in Spanish taste.22

As the historian Thomas Dandelet has explained, the power of the Spanish faction was demonstrated through Spanish influence on conclaves, pensions, and rituals. The most effective way of doing so would have been to select a reasonable Pope with whom the Spanish king could maintain amicable bonds.23 Paul V was without doubt a ‘Spanish Pope’, and his architect from Utrecht seems to have been the first open door for the Utrecht Caravaggisti to the powerful clienteles of the Spanish faction. Giovanni Vasanzio may not have paid a penny for the painters, but if the Dutch painters had a reliable fatherly patron in the eternal city, it seems that he must have been the one.

Notes

1 Marchetti 2005, p. 71.

2 Sturm 2015, p. 2-3.

3 For Domenico di Gesù Maria: Freiberg 2005, passim; Lorizzo 1995, p. 163-164; Paolini 2019, p. 72, 94-95, 301-302.

4 Orbaan/Hoogewerff 1911-1917, vol. 2, p. 363.

5 Hoogewerff 1942, p. 50-51.

6 The information on his activity as a cabinetmaker with the workshop in the Via Giulia is kindly provided by Gert Jan van der Sman.

7 Ottenheym presumes that he remained in contact with Holland, perhaps through visiting artists, because some of his architectural designs were posthumously published in Amsterdam. Ottenheym 2013, p. 73.

8 Bertolotti 1880, p. 82.

9 Johanna Peunis (van Diest), mother of Jan van Santen, and Cornelia Peunis (van Diest), mother of Willem van Wede, are sisters. Koenen 1901.

10 Roethlisberger/Bok 1993, p. 631. It is also interesting to know that Abraham Bloemaert witnessed the execution of the marriage contract in 1623 between his niece, Mechtelt de Roij, and another ‘Willem van Weede’, who might also be relative of the deceased painter. Ibid., p. 627.

11 Nicolson 1958, p. 36-37.

12 Giustiniani’s importance for the painters from the north is also significant, and the issue is argued by Megna and Lorizzo. He shared the cultural and religious networks with the people argued in the current paper. Megna 2003, Lorizzo 2015.

13 Paolini 2019, p. 93-96.

14 Paolini 2019, p. 95.

15 Paolini 2019, p. 301-302.

16 For the basic information of the work: Roethlisberger/Bok 1993, p. 68-69; Papi 1999, p. 130-131.

17 Lorizzo 1995, p. 162-163.

18 For the iconographical significance of St Joseph for the Discalced Carmelite: Lorizzo 1995.

19 Cantatore 2007, p.123.

20 It seems noteworthy as well that it was Domenico di Gesù Maria who prompted the restauration of the Bramante’s Tempietto in San Pietro in Montorio in late 1620s. Freiberg 2005.

21 Dekker 2017, p. 53. It should be noted, however, that Van Baburen’s father was in all probability Protestant. For Van Baburen’s father and his faith: Franits 2013, p. 2.

22 Weber 2015-2016.

23 Dandlet 2001.