3.4 Public Commissions

Miel’s public commissions provided the best opportunity for him to come into contact with the Roman artistic milieu, through which he was able to establish his own personal style. Miel made his debut in the public arena in 1651, in the church of San Martino ai Monti, where he painted The Baptism of the Sultan of Iconium [20].1 Although this was his first work in fresco, it already shows a mature language with few inaccuracies and signs of hesitation, and undeniable similarities with the manner of Andrea Sacchi. There is a strong connection between Miel’s fresco and the decorative cycle in San Giovanni in Fonte, which was an important site of new artistic developments in Rome. The decoration of San Giovanni in Fonte (1639–1650) was directed by Sacchi and involved the work of other established artists including Giacinto Gimignani (1606–1681), Andrea Camassei (1602–1649), Carlo Magnone (1620/1621–1653) and Carlo Maratti (1625–1713).2 The composition of Miel’s fresco in San Martino ai Monti is clearly derived from the painting depicting The Baptism of Christ by Sacchi in San Giovanni in Fonte. In addition, the figure of the boy in the foreground is based on the figure with the helmet in Maratti’s fresco, Constantine establishing the Christian Religion and ordering the Destruction of Pagan Idols [21], a work that Miel clearly studied carefully in these years.

The cycle in the Lateran Baptistery also had a fundamental influence on what can be regarded as Miel’s greatest achievement in the field of history painting: the Stories of St Lambert in Santa Maria dell’Anima, the German church in Rome. Thanks to the accounts of the Monte di Pietà, it is possible to date this cycle securely to 1652–1653, just after Miel’s commission for San Martino ai Monti. The archival documents also reveal the involvement of the Genoese Monsignor Giacomo Franzone (1612–1697).3 Franzone managed the bequest of Egidius van de Vivere, the patron of the chapel, who had died in 1648, and it was Franzone who authorised the payment for the decoration of the chapel. It is therefore possible that Franzone played an active part in commissioning Miel to produce the St Lambert cycle, as suggested by Giovanni Battista Passeri.4 The identification of the involvement of Franzone in this matter is particularly relevant because it would be the first evidence of a close connection between Miel and the Genoese prelate. This connection is confirmed by the artist’s wills, in which he nominated Agostino Franzone (1614–1705), the brother of Giacomo, as his universal heir.5

As argued above, the decorative cycle at San Giovanni in Fonte played a crucial role in the development of Miel’s style. Once again we see the influence of Maratti’s work in the details of Miel’s frescoes in Santa Maria dell’Anima, such as the idea of the figure of a man destroying a Classical sculpture. In comparison to the slightly earlier fresco in San Martino ai Monti, however, here we can see a remarkable use of bright colours and a fluidity of brushwork, the result of Miel’s interest in the work of Nicolas Poussin and Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione.6 The latter may also have been an inspiration for Miel in his genre paintings. Miel’s attempt to elaborate on Castiglione’s style and composition is evident in his Bacchanal with Faun and Nymph from the Corsini collection.7 Once again the colours, the fluency, and even the subject recall the work of Castiglione, which was widely available on the Italian art market. The bacchanal subject was realized by Castiglione on more than one occasion, for example the Bacchanal at the Galleria Sabauda in Turin and the paintings in the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg and the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico.

20

Jan Miel

Baptism of a Roman General by a saint, 1651

Rome, San Martino ai Monti

21

Carlo Maratta after Andrea Sacchi

Constantine establishing the Christian religion and ordering the destruction of pagan idols, 1648

Rome, San Giovanni in Fonte

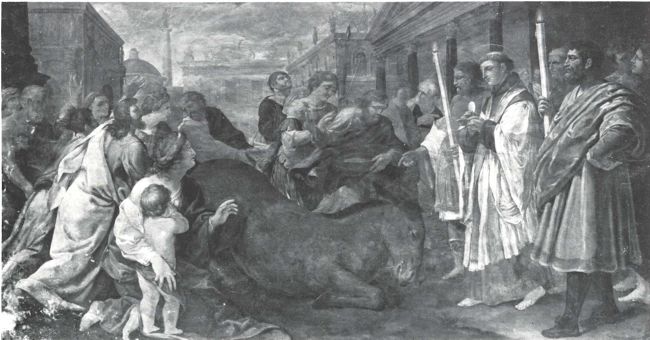

22

Jan Miel

Saint Anthony of Padua and the miracle of the severed foot, c. 1655-1657

Rome, San Lorenzo in Lucina

23

Jan Miel

Saint Anthony of Padua and the miracle of the kneeling ass, c. 1655-1657

Rome, San Lorenzo in Lucina

Miel’s ability to build on the most up-to-date developments in Roman art was not based only on the work of Andrea Sacchi and his workshop. In two canvases dedicated to the miracles of St Anthony of Padua [22–23], created for the chapel of that saint in the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina, Miel seems to align himself with the frescoes of the same subject in the Albertoni Paluzzi Chapel in Santa Maria Aracoeli, which were probably realized by the Lorraine artist Charles Mellin (1598–1649) [24-25].8 In San Lorenzo in Lucina Miel employed the same layout but emphasized the chiaroscuro effect, and, as we have seen him do in other paintings, enriched the scene with narrative details. For example, in The Miracle of the Mule Miel elaborated on the subject by including the delightful detail of the elderly man who, incredulous at what he is seeing, puts on his glasses.

24

attributed to Charles Mellin

Saint Anthony of Padua and the miracle of the severed foot, 1622-1649

Rome, Santa Maria in Aracoeli

25

attributed to Charles Mellin

Saint Anthony of Padua and the miracle of the kneeling ass, 1622-1649

Rome, Santa Maria in Aracoeli

Miel’s public career in Rome ended with the most important type of commission that an artist could receive at that time: three papal commissions by Alexander VII (1599–1667). In 1656 Miel was put in charge of painting the large fresco of The Crossing of the Red Sea (200 x 500 cm) in the so-called Gallery of Alexander VII in the Quirinal Palace, under the direction of Pietro da Cortona.9 Considering that Miel had arrived in Rome some twenty years earlier, seemingly without any experience in the field of fresco painting, his commission for the Quirinal Palace reveals both his versatility and the scale of his achievement as an artist. The fresco itself is composed of a crowd of figures, all with different poses and expressions, as was in keeping with both the subject matter and its eminent position in the Gallery. Here Miel quoted from important early 17th-century Roman sources such as St Susanne by François Duquesnoy (1597–1643), whose drapery is echoed in the figure of Moses. Another source of inspiration was the work of Annibale Carracci (1560–1609) in the celebrated Farnese Gallery: in particular, from the central scene of The Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne Miel took the detail of the maenad carrying a wicker basket on her head, and adapted it for the woman in the background of the Crossing who is rescuing her baby.

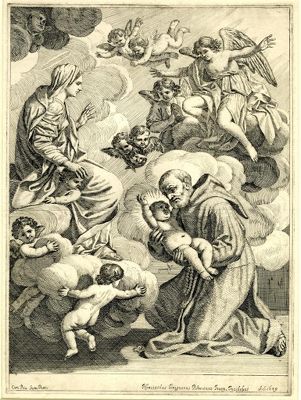

Two other commissions further attest to Pope Alexander VII’s support of Miel: two engravings for the new edition of the Missale Romanum, published in Rome in 1662 [26–27],10 and the frescoes of biblical scenes in the private chapel of the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican, produced in February 1657. These frescoes were thought by scholars to be lost, but I successfully identified them among the paintings of the piano nobile of the palace, which were given incorrect attributions in the past.11 These were Miel’s final works in Rome before he left at the end of 1658 for Turin, where he was appointed ‘pittore ordinario’ (court painter) by the Duke of Savoy, Charles Emmanuel II.12

26

Etienne Picart after Jan Miel

The birth of the Virgin Mary, c. 1662

Whereabouts unknown

27

Guillaume Vallet after Jan Miel

The assumption of Mary, c. 1662

Whereabouts unknown

Outside Rome: Chieri (Piedmont) and Lerici (Liguria)

Before Miel left Rome he produced two altarpieces for locations outside the city. The first was made for the Cathedral of Chieri, a small city near Turin. It is signed and dated ‘Gioa Miele fecit et inue. Roma 1651’.13 Its subject, The Virgin and St Anne presenting the Christ Child to St Anthony of Padua, St Barbara, St Ursula, St Agatha and St Catherine of Alexandria [28], must have been chosen by the patron, Count Baldassarre Robbio di San Raffaele (?–1662), for it was Robbio who, upon his acquisition of the Chapel of St Anne in 1648, added the dedication to St Anthony of Padua. In addition, Robbio’s first wife was called Caterina, and one of his daughters became a nun at the monastery of Sant’Andrea e Santa Maria in Chieri and took the name Orsola Caterina.14

Given the current state of research, it is not possible to establish whether there was a connection between the commission in Chieri and Miel’s nominee as court painter to the house of Savoy. Baldassarre Robbio di San Raffaele did hold the position of ‘Commissaro generale dell’Artigliera di Sua Altezza Reale’15 from at least the 1630s, but we have yet to find a stronger link between Miel and Duke Charles Emmanuel II and his entourage. Aside from this, what needs to be stressed is that the commission for the Chieri altarpiece followed swiftly on the tail of Miel’s public debut at San Martino ai Monti, indicating that by 1651 Miel was already considered to be a good history painter. The Chieri painting is particularly important because it is one of the few altarpieces by Miel. From what we know of his public commissions, it is clear that he specialized in the production of frescoes rather than altarpieces. In the context of the competitive art market of 17th-century Rome, being able to work in fresco was a crucial skill required to fulfill a patron’s requests.16 As demonstrated by Miel’s participation in the Quirinal Palace, it was also one of the best ways to take part in important collective decorative schemes.

The altarpiece in Chieri is also interesting because it can be read as a summary of Miel’s formation as an artist. In the upper register, the facial features of the saints seem to be idealized and recall the typical figures of Andrea Sacchi, such as the figures in the fresco of The Triumph of Divine Wisdom in the Palazzo Barberini or the altarpiece of St Helen and the Miracle of the True Cross now in the Chapter House of St Peter’s. In the lower register, by contrast, the figure of St Anthony is realized in a more naturalistic way; see for example the detail of the saint’s wooden clogs. In addition, the central group is presented in strong chiaroscuro, a constant trait of Miel’s pictorial production and an aspect of his work commented on by the sources.17 The altarpiece is clearly influenced by the language of Roman painting, and encouraged the diffusion of its style outside Rome. The composition of the painting, arranged along a diagonal, is influenced by contemporary works by Giacinto Gimignani that Miel had the opportunity to see in San Giovanni in Fonte and in Santa Maria dell’Anima. Miel could have been influenced by Gimignani’s Virgin of the Rosary sent from Rome to Prato Sesia (near Novara) around 1648–1649, and by the engraving of St Felix holding the Christ Child, signed and dated ‘Hycinthus Gimignanus Pistoriensis incidebat A S 1649’ [29].18 Miel and Gimignani were also both employed in the illustration of the second volume of De Bello Belgico by the Jesuit Famiano Strada, printed in Rome in 1647 [30-31]. Miel’s Chieri altarpiece would in turn become a model for other painters working in Piedmont, such as the talented Charles Dauphin (1620?–1677), court painter to the Carignano family, who realized another version of The Virgin presenting the Christ Child to St Anthony of Padua [32] for the church of the same name in Carmagnola, near Turin.19

28

Jan Miel

The Virgin and St Anne presenting the Christ Child to St Anthony of Padua, St Barbara, St Ursula, St Agatha and St Catherine of Alexandria, dated 1651

Chieri, Duomo di Chieri

29

Giacinto Gimignani

Saint Felix holding the Christ Child, dated 1649

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1874,0808.768

30

Giacinto Gimignani

The capture of Tournai by the Spanish army of the Duke of Parma in 1581, dated 1647

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1854,0812.22

31

Jan Miel

The capture of Bonn in 1588, c. 1647

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-80.064

The other altarpiece that Miel produced before he left Rome, The Assumption with St Jerome, King David, Salomon and other Prophets [33], was sent to Lerici, a small town in Liguria near La Spezia. The painting is signed and dated: ‘JAN MIELE FECIT/ ROMAE 1657’. Giovanni Romano has examined in depth the circumstances of the commission by the local Botto family.20 However it remains difficult to trace the link between the Botto family and Miel, although it is possible that the brothers Giacomo and Agostino Franzone, who were originally from Genoa, may have played a mediating role.

The Lerici altarpiece – which like the Chieri altarpiece is bathed in golden light, with a strong chiaroscuro – reveals another of Miel’s sources: the work of Guido Reni. It recalls Reni’s Assumption painted for the church of the Gesù in Genoa. The clear correspondence between the upper sections of the two paintings, and even the tenderness of the Virgin’s face and the inclination of her head, allow us to think that Miel may have seen Reni’s painting in person, perhaps during his trip around northern Italy in 1654.21 An even closer relationship can be identified between the Lerici altarpiece and another work by Guido Reni: The Fathers of the Church disputing the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception in the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg. Both paintings testify to the intensity of the debate surrounding the dogma of the Immaculate Conception in the 17th century.22 This would explain why Miel initially depicted an inverted crescent under the feet of the Virgin, a traditional iconographic symbol of the immaculate status of the Virgin, and later decided to partially conceal it under the clouds.23 If we compare the two works from a stylistic point of view, we can see further evidence of the strength of Reni’s influence on Miel. This is especially evident in the choice of colours and in the poses of the prophets, such as the prophet on the left in Miel’s painting who is absorbed in reading, or the prophet in the background who has his hands on his head and is carefully reading the Holy Scriptures, both of which are taken directly from Reni. These similarities lead one to suppose that Miel was able to study Reni’s painting in person. Unfortunately we do not know who commissioned Reni’s painting, or what its original location was, although its size alone (273.5 x 184 cm) suggests that it was originally intended for an altar. If Miel did actually see The Fathers of the Church, it must have been in Rome from at least the 1650s, if not before – a helpful step in establishing the provenance of Reni’s painting.24

32

Charles Claude Dauphin

The Virgin presenting the Christ Child to Saint Anthony of Padua, c. 1650-1677

Carmagnola, Sant' Antonio di Padova

33

Jan Miel

Mary of the Immaculate Conception with Saint Jerome and prophets, dated 1657

Lerici (La Spezia), San Francesco (Lerici)

Notes

1 On the dating of San Martino ai Monti: Sutherland Harris 1964, p. 115–120.

2 The cycle is the most important decorative scheme carried out between the pontificates of Urban VIII and Innocent X (1574–1655). Gimignani, Camassei, Magnone and Maratti painted five Stories of the Emperor Constantine in fresco, and Sacchi painted eight canvases depicting the Life of St John the Baptist: Sutherland Harris 1977, p. 19–22, 84–89; Tempesta 1999, p. 45–52.

3 Rome, Archivio di Stato, Monte di Pietà, Libro Mastro 91 (1652), ff. 273sx–273dx, 948sx, and Libro Mastro 92 (1653), f. 209sx; already cited without in Erwee 2014–2015, vol. 2, p. 189 note 75.

4 Passeri 1772, p. 226–227. The question is considered in Gaja (fortcoming).

5 Bertolotti 1880, p. 40–42; Bertolotti 1885, p. 22–23; Kren 1978, vol. 1, p. 13, 21 note 1; Vesme 1963–1982, vol. 2, p. 687–688. Baldinucci also says that Miel was ‘forte obbligato coll’Eminentissimo Franzona, e col Cavaliere suo fratello, per mille ricevuti benefizi’: Baldinucci 1767–1774, vol. 17, p. 36.

6 The brightness of the blue lapis lazuli and the purity of the whites, as well as the fluency in shaping the draperies, have similarities with Castiglione’s Immaculate Conception with SS. Francis of Assisi and Anthony of Padua, painted in Rome in 1650 and now in the Minneapolis Institute of Art: Gabrielli 1955, p. 261–262. Miel might have met Castiglione when they worked for the aforementioned Marquis Tommaso Raggi. From Raggi Castiglione received the large sum of 380 scudi between February 1647 and January 1650. Miel was paid between 1646 and 1651: Curzietti 2014A, p. 170–171.

7 Now in the collection of the Fondazione Roma. A label on the back states that in the 19th and 20th centuries the painting was in the collection of Beatrice Corsini (1868–1955), who may have inherited it from her father, Tommaso Corsini (1835–1919), Prince of Sismano: Gandolfi 2019, vol. 1, p. 104 cat. 30. I thank Benappi Fine Art for bringing to my attention this painting and the unpublished note written by Vittorio Natale in 2011.

8 Recent criticism is not unanimous in attributing these two frescoes to Mellin. Abbot Filippo Titi wrongly attributed these scenes to Girolamo Muziano (1532–1592), who painted in the same chapel: Titi 1686, p. 172. Johanna Heideman proposed to assign them to Miel or to Pier Francesco Mola (1612–1666). Giorgio Falcidia favoured Mellin. Recently it has been suggested that these works might be by Nicolas Labbé (1608–1647), Mellin’s assistant: Heideman 1982, p. 129, 131, notes 43–45; Falcidia 1984, vol. 2, p. 641–644; Malgouyres 2007, p. 238–239. If the frescoes were definitely by Mellin that would be interesting, given that Baldinucci noticed Miel’s affinity with the Lorraine artist. In fact, describing the fresco in San Martino ai Monti he reported that Miel ‘s’ingegnò di seguitar lo stile di Carlo Lorense’: Baldinucci 1767–1774, vol. 17, p. 34. On Miel’s paintings in San Lorenzo in Lucina: Toesca 1962, p. 135–136; Bodart 1970, vol. 1, p. 407–408.

9 On the Gallery: Wibiral 1960 (especially p. 141–142, 163); Briganti 1962, p. 44–50; Negro 1999; Pasti 2006; Negro 2009; Negro 2017.

10 Miel provided the engravers Étienne Picart (1631/1632–1721) and Guillaume Valet (1632–1704) with preparatory drawings for The Birth of the Virgin and The Assumption of the Virgin. Because of his celebrity as a painter of bambocciate Miel’s activity for the Missale has not drawn the attention of scholars. Most of the painters active in the Gallery of Alexander VII were also involved in its production: Graf 1998.

11 The research was undertaken during my PhD at the University of Turin. The rediscovered frescoes are analysed in depth in Gaja 2022.

12 Turin, Archivio di Stato, Sezioni Riunite, Camera dei conti, Piemonte, Patenti controllo finanze, art. 689, 12 November 1658, mazzo 138, f. 65r; already in Vesme 1963–1982, vol. 2, p. 686.

13 In the 19th century Canon Bosio misread the date as ‘1654’ instead of ‘1651’: Bosio 1878, p. 85. The correct date emerged during the restoration in 1987: Di Macco 1989, p. 196–197 cat. 222.

14 Robbio’s family is named in his will, drawn up in Chieri on 24 May 1650. Caterina (who died before 1650) and Baldassarre had five children: Countess Vittoria Maria, wife of Giovanni Battista Tana, Count of Limone; Orsola Caterina; Lelio; Francesco; and the canon of the Cathedral, Ottaviano. Chieri, Archivio Storico Filippo Ghirardi, articolo 6, paragrafo 7, numero 74, folios not numbered. The reason for the presence of St Barbara and St Agatha is still unclear. There is no mention of the painting in Baldassarre’s will.

15 Turin, Archivio di Stato, Sezioni Riunite, Uffici di Insinuazione, Tappa di Torino, Atti pubblici, 11 novembre 1643, libro 12, registro 1653, f. 165r.

16 For an overview of the Roman context: Briganti 1982, p. 99–110; Briganti 1989, p. 23–26; Schleier 1989, vol. 1, p. 399–460.

17 The abbot Luigi Lanzi stated that Miel was a painter ‘di bel chiaroscuro, non però scompagnato da una gran delicatezza di colorito’: Lanzi 1809 (1974), vol. 3, p. 249.

18 The painting was commissioned by a local family, the Furogotti, several members of which emigrated to Rome: Venturoli 1989, p. 233–234 cat. 257; Dell’Omo 1994, p. 104; Dell’Omo 1999, p. 233, 236.

19 On Dauphin: Fohr 1982; Di Macco 1984; Cifani, Monetti 1988, p. 319–324; Cifani, Monetti 1998.

20 Romano 2001.

21 As testified by his first will, drawn up in Rome in 1654, where Miel names Agostino Franzone as his universal heir: there he arranges a repayment to Agostino who had financed his trip in northern Italy: Bertolotti 1880, p. 140–141. It is fair to think that Agostino may have asked Miel to visit Genoa as well, perhaps to settle some business there.

22 The dogma was finally approved in 1854 by Pope Pius IX. On this topic: Zuccari 2005, p. 64–77; Anselmi 2008.

23 This detail appeared during the restoration: Romano 2001, p. 64–65.

24 Matteo Biffis was able to trace one stage of the painting’s provenance to the collection of Cardinal Giacomo De Angelis (1611–1695). However, that is not mentioned until 1687: Biffis 2018, p. 65–76. Scholars tend to date the picture around the end of 1610s and the beginning of 1620s: Pepper 1984, p. 250; in that case the Cardinal could not have been the original patron, since he was born in 1611.