3.2 A Matter of Style: Artistic Exchanges in the Roman Milieu

Jan Miel is first documented in Rome on 14 November 1636, when he took part in a meeting at the Accademia di San Luca as a member of the Flemish community. On that date Miel attended a reconciliation between Italian and foreign painters regarding an annual taxation that had been imposed in 1633 by Pope Urban VIII (1568–1644).1 This first mention of Miel in Rome is important, because it proves that by this date he was already well integrated into the group of Northern artists working there. As noted above, this is also one of the few documented instances of contact between Miel and Van Laer, as recorded in the registers of the Accademia.2

While we have no further archival evidence of a close relationship between the two painters, such as an apprenticeship, Miel’s first paintings clearly speak the same artistic language as those of Van Laer [5]. For example, two small bambocciate paintings signed and dated by Miel, in the Louvre Museum, are stylistically very close to the work of Van Laer. These are The Bocci Players [6], signed ‘Gio Mele fecit/ 1633’ and The Shoemaker [7], signed ‘? Mele fecit/ 163?’.3 The existence of these paintings that are clearly influenced by Van Laer and date to 1633 indicates that Miel was already in Rome at that date, three years before his first documented presence in the city. It is of course possible that Miel was in Rome even earlier than 1633, but there are no archival documents or artworks to substantiate this.

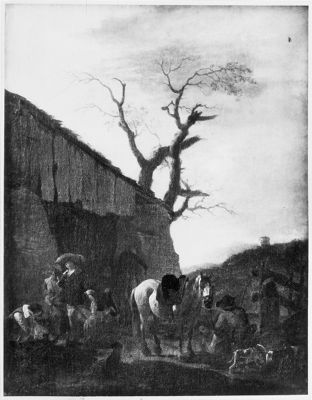

5

Pieter van Laer

Rustende jagers bij een herberg (de staande jager is een vrouw in mannenkleren)

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv./cat.nr. 1229

6

Jan Miel

Bocci players, dated 1633

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. RF 1949 25

7

Jan Miel

The shoemaker, 1633

Besançon, Musée des Beaux-Arts et d'Archéologie de Besançon

Around the middle of the 1630s, and increasingly in the 1640s, in order to fulfil his patrons’ requests Miel developed a complex and yet personal style that was the result of an artistic exchange between Roman visual culture and Flemish genre painting. The 1640s marked a significant diffusion of the bambocciate thanks to the interest of important collectors, such as the Barberini family. In this regard, two paintings – both in private collections – are particularly relevant. In The Mandolin Player [8] on the harness of the white horse in the middle there is an escutcheon with the double coats of arms of Taddeo Barberini (1603–1647), Prefect of Rome, Prince of Palestrina and nephew of the Pope, and his wife Anna Colonna (1601–1658).4 The other work [9] is a small genre painting depicting a charming group of animals and a drinking trough that is carved with the coat-of-arms of Pope Urban VIII, a detail that helps us to date the painting no later than 1644, the year of the Pope’s death.5 As noted by Thomas Kren, the inclusion of two camels among the animals was probably done at the express request of the Pope.6 The dating of these two paintings also reveals an early response by collectors to the trend for bambocciate paintings. The Barberini family were clearly interested in collecting this kind of painting: this is further suggested by the 1634 inventory of the collection of Cardinal Francesco Barberini (1597–1679), Urban’s nephew, which records the presence of a painting by Van Laer.7 It is also worth noting that during this decade the production of bambocciate was not the exclusive domain of Northern artists. Italian painters also began to work in this genre: Michelangelo Cerquozzi (1602–1660), also known as Michelangelo delle Battaglie, was one of the first in Rome to take on this style of painting [10].

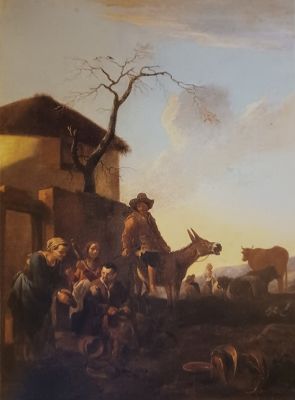

8

Jan Miel

A stop in front of an inn with a mandolin player on a donkey, c. 1640

Private collection

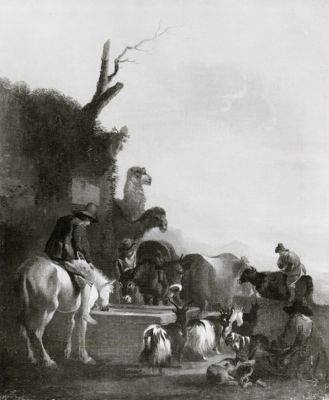

9

Jan Miel

Shepherds with cattle and two camels at a trough, c. 1640-1644

Private collection

10

Michelangelo Cerquozzi

The trough

Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica (Rome), inv./cat.nr. 1021

The most important evidence of a connection between Miel and the Barberini circle in the early 1640s is the large painting of Urban VIII visiting the Church of the Gesù, made in collaboration with Andrea Sacchi and the painter of architectural perspectives Filippo Gagliardi (1606/8–1659) [11]. Commissioned around 1640–1641 by Cardinal Antonio Barberini (1607–1671), nephew of the Pope and brother of Cardinal Francesco and Prince Taddeo, this was one of Miel’s first history paintings. If we examine the parts for which Miel was responsible we can see how his style was still rooted in Flemish and genre painting. According to the inventory of the collection of Antonio Barberini, drafted after his death in 1671, the work on the picture was distributed as follows: ‘Prospettiva, mano di Filippo Gagliardi le principal figure mano del Fu S.r Andrea Sacchi, il restante di Gio. Miele’.8 Here ‘restante’ refers to the vivid crowd that animates the interior of the Gesù, with the exception of the Pope and his entourage in the middle, which are by Sacchi’s hand. The detail of the carriages and gentlemen in the foreground, which mark the border between the ceremony inside the church and daily life outside, is also by Miel. Each figure has its own individual pose and expression, resulting in a lively and animated crowd. As far as we know, this was the first time that Miel translated the small scenes of daily life onto a much grander scale, anticipating the series of large canvases he would go on to to produce for Marquis Tommaso Raggi (1575–1679) of Genoa.

The painting of Urban VIII visiting the Church of the Gesù also marks a crucial turning point in Miel’s career, because it clearly documents the existence of a connection with Andrea Sacchi, a connection that could already be perceived in Miel’s style. This collaboration between the two artists is cited in Baldinucci’s biography,9 but he read this episode as the reason behind the breakup of their relationship. Baldinucci mentions a harsh fight between Miel and Sacchi, caused by Sacchi’s disgust with the lack of decorum of the bambocciate.10 In Baldinucci’s opinion, their quarrel led Miel to abandon the production of canvases of daily life in order to study, improve his technique, and dedicate himself to history painting.11

11

Jan Miel and Andrea Sacchi and Filippo Gagliardi

The Celebration of the Centenary of the Jesuit Order in the Gesù in 1639, c. 1641-1642

Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica (Rome), inv./cat.nr. 1445b/ F.N. 3573

12

Jan Miel

Carnival in the Piazza Colonna, Rome, c. 1650

Hartford (Connecticut), The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 1938.603

13

Jan Miel

Market scene in Prati outside Rome with the dome of Saint Peter's in the background, on the left side of the foreground carnival-goers, dated 1650

Antwerp, The Phoebus Foundation

Contrary to what Baldinucci tells us, it was precisely during this time that Miel further explored the expressive possibilities of daily life genre painting, expanding the composition, increasing its complexity, and depicting larger crowds, until ultimately he created a model for bambocciate painting.12 A telling example is the series of large canvases commissioned between 1646 and 1651 by Marquis Tommaso Raggi, another of Miel’s early patrons. Raggi was a passionate collector, as described by Bellori, and owned paintings by both Flemish and Italian masters, including Van Dyck and Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione (1609–1664).13 Raggi, who was on good terms with Pope Urban VIII, commissioned from Miel five large rectangular paintings in which Miel definitively crossed the boundaries, moving from the small format and transposing the features of the bambocciate on to a monumental scale. Three out of five of these paintings have been identified by scholars: Carnival in the Piazza Colonna in the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford [12]; Feast at a Fair in Prati outside the Walls of Rome, recently sold by Christie’s [13], and Limekiln, collection of the Bank of Italy. Together with Monuments of Ancient Rome and Feast of Peasants, which are still missing, these paintings comprise ‘the most unusual and ambitious unified program of bambocciate ever undertaken in Rome’, as recognized by Thomas Kren.14

During this period, Miel also produced paintings on the theme of the carnival, such as Carnival in Rome, now in the Prado. The Prado painting is particularly important because it is one of the few genre paintings by Miel to be signed and dated by him (1653) [14]. It represents a type of painting that met the taste of collectors and was very popular in the 17th century. The existence of these works shows that Baldinucci was wrong to state that Miel, after the argument with Sacchi, abandoned bambocciate in favour of history painting.

During this decade of great experimentation in genre painting Miel increased his activity in the field of history painting. His little-known early activity as peintre-graveur and his painting on copper of The Assumption of the Virgin suggest that upon his arrival in Rome he was already capable of handling both genres. Another work of the 1640s is the virtually unknown Mater Dolorosa [15], signed and dated 1647, which was clearly made for the flourishing market in works for private devotion, a function that can be inferred from the painting’s intimate subject matter and its small size.15 Contrary to the contemporary sources that suggest that Miel turned to history painting as the only way to elevate his artistic production, he showed a certain versatility, working in both history and genre painting, according to his patrons’ tastes and in order to gain his own place in the Roman art market.

14

Jan Miel

Carnival in Rome, dated 1653

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. P001577

15

Jan Miel

Mary as Mater Dolorosa, dated 1647

Notes

1 Hoogewerff 1953, p. 30–36. In the current state of knowledge it is not possible to establish whether Miel was part of the Schildersbent (an informal organisation of Northern painters active in Rome). Due to its unofficial nature, a list of its members does not exist. However, we know from some contemporary sources that nicknames were used by the group. We also know that Miel went by the nicknames ‘Bieco’ and ‘Honingh-Bie’, which suggests that he may have taken part in their meetings. ‘Honingh-Bie’ (that is, honeybee) in particular seems to have been a play on Miel’s surname, since the Italian word for honey is ‘miele’. For the list of Miel’s nicknames: see Jan Miel in RKDartists. For the Schildersbent I refer to the recent research of Suzanne Baverez, including her article in this publication.

2 Also present at the meeting were Herman van Swanevelt (1603–1655) and Michelangelo Cerquozzi (1602–1660). Pietro da Cortona was then ‘principe’ of the Accademia, while Sacchi held the position of ‘consigliere’: Rome, Archivio Storico dell’Accademia di San Luca, Libro originale delle Congregazioni ossiano verbali delle medesime, 1634–1674, vol. 43, fol. 17v–18v; already in Hoogewerff 1913, vol. 2, p. 49–52.

3 The Shoemaker is on loan to the Musée des Beaux Arts de Besançon: Kren 1978, vol. 2, p. 8 cat. A1, p. 35–36 cat. A19; Trezzani 1983B, p. 102; Rosenberg 1989, p. 134. These are Miel’s earliest known signed works, but I believe that the catalogue of Miel’s works should start with the small copper painting of the Assumption.

4 Kren dated the painting to around 1640: Kren 1978, vol. 1, p. 150; vol. 2, p. 58–59 cat. A38. On the career of Taddeo Barberini: Merola 1964, p. 180–182. I am currently consulting the Barberini archive at the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana in Rome, but for the moment I have not found evidence of other commissions made by Taddeo to Miel. I intend to extend my research to the Colonna archives, searching for traces of the involvement of Anna Colonna. In this respect it is particularly interesting that Passeri mentions a fresco in the (destroyed) monastery of Regina Coeli depicting St Sebastian, commissioned from Miel by Anna Colonna herself: ‘avendo la Principessa D. Anna Colonna […] eretto un nuovo Monastero di Carmelitane Scalze alla Longara […] e bisognando farvi alcune cose di dentro di pittura, Giovanni per provare a dipingere a fresco volle anch’egli farvi la sua parte. Fu questo nell’anno 1649’: Passeri 1772, p. 225–226. Due to a lack of documents it is not clear whether Miel did realize this painting, but the fact that Passeri mentions a precise year is noteworthy. On Anna Colonna’s patronage of the monastery and church of Regina Coeli: Curzietti 2014B.

5 Formerly in Rome with the dealer Sestieri, now in a private collection: Kren 1978, vol. 2, p. 74–75 cat. A54.

6 Kren 1978, vol. 1, p. 153.

7 ‘E più entro un quatro largo p[al]m[i] 3 – largo 2½ fatto dal Sig.re Pietro detto Barbono [Bamboccio] con diverse figurine de notte con francesi Zingare diversi con altre animali’. It is interesting that Francesco Barberini received the painting from Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), who seems to have played the role of mediator: ‘un quadro con una Zingara dato al S. Card[ina]le per le mani di S. Cav[aglie]re Bernini’ – Aronberg Lavin 1975, p. 3, note 18.

8 Aronberg Lavin 1975, p. 292, note 1.

9 ‘Andrea Sacchi […] strinse con seco [i.e. Jan Miel] ordinaria amicizia: e non solo volevalo del continovo a disegnare nella propria Accademia; ma dovendo egli colorire in un gran quadro la mostra che fa la Cavalcata pontificia, lo volle in aiuto, e condusse la gran tela’: Baldinucci 1767–1774, vol. 17, p. 34–35.

10 ‘[…] non andò molto, che […] Andrea forte si disgustò con esso [i.e. Jan Miel], e venuto in collera gli disse che egli se ne andasse a dipingere le sue bambocciate’: Baldinucci 1767–1774, vol. 17, p. 35. Passeri does not mention their connection or the painting they made together.

11 ‘Allora Giovanni, vedendosi con tali parole punto nel vivo si rimesse con gran fervore a fare studio sopra le grandi figure: e consigliato dal Bernino, con cui aveva pure contratta non poca amistà, deliberò di fare un viaggio per la Lombardia, come quegli ancora che non prezzando più che tanto la propria grandissima abilità nel fare piccole e mezzane figure di capricci e bambocciate, ardeva di desiderio di condurre agli ultimi segni di perfezione la propria maniera nell’inventare, e colorire in figure grandi’: Baldinucci 1767–1774, vol. 17, p. 35. Thus according to Baldinucci in these years Miel was a friend of both Sacchi and Bernini, two of the most important artists of 17th-century Rome.

12 Briganti 1983, p. 12.

13 On Tommaso Raggi: Boccardo 2004. The commissioning of Miel is documented in Curzietti 2014A, p. 180–181.

14 Kren 1978, vol. 2, p. 26–29 cat. A15; Curzietti 2014A, p. 170–171.

15 The painting was sold by Sotheby’s (London, Old Master Paintings, 10 December 2001, lot 502). In the catalogue the date is given incorrectly as ‘1637’ instead of ‘1647’. The painting is perhaps the same as that described as ‘Vierge de doleur’ and sold in Paris in 1787, although the size is slightly different (its description is as follows: ‘Une Vierge de doleur, elle est vue assise les mains jointes, le regard tourné vers le Ciel, la tête est couverte d’un voile jaune & est enveloppée d’une draperie bleue. Les Tableaux de ce genre sont rares, & celui-ci-joint à cette qualité le mérite d’un beau faire, & d’une belle expression’). In the sale that painting is recorded as 19 x 13 inches, approximately 48.5 x 33 cm, whereas Sotheby’s version is 52.5 x 39.5 cm. It is also possible that Miel did more than one version of that subject: Paris 1787, lot 44, p. 20; Kren 1978, vol. 2, p. 181 cat. C109 (as lost).